#4 – Février / February 2022

Jan Baetens

An interview with J.R. Carpenter

Jan Baetens: A multimedia artist initially trained in drawing and sculpture, you rapidly started working in what one might call, with a modern cliché, the expanded field of writing. What were the main motives of that move, and how would you define the lasting influence of your visual training in your writing?

J.R. Carpenter: It wasn’t a move. I’ve always written. I’ve kept a journal since the age of eight. In high school, I taught myself calligraphy, and I spent a summer studying life drawing and anatomy at the Art Students League in New York. I became obsessed with line. That line of inquiry has not left me. I still do most of my thinking by writing longhand.

My training in Fine Art was not visual so much as it was material. Writing, for me, has always been a material practice. In art school, I embroidered text into blankets, crocheted text into three-dimensional shapes, incorporated found text into artist’s books, and published my own writing in small photocopied zines. For written assignments, I handed in hybrid critical-creative essays illustrated with found diagrams from science and mathematics textbooks, without the faintest inkling that there was anything unusual about these documents. I wrote distributed narratives in USNET news groups. I wrote non-linear hypertextual narratives. I wrote art reviews and catalogues essays. I wrote scripts for live performance. One of my first jobs after graduation was writing scripts for Radio Canada International.

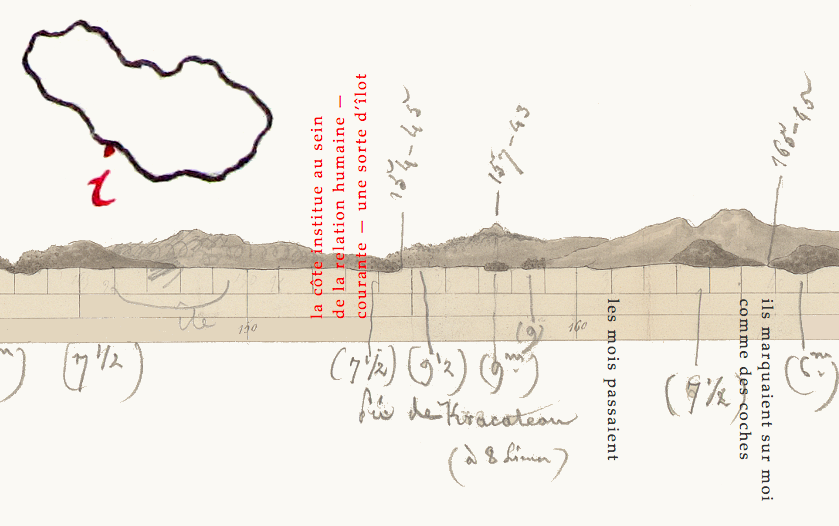

The great advantage to never having studied writing was that there was never anyone to tell me there were wrong ways to write. I continue to think and write critically, creatively, and materially about the fine line between writing and drawing. Maps and diagrams figure prominently in my web-based work. My first novel, Words the Dog Knows, incorporated line drawings and handwriting. In my PhD thesis, Writing Coastlines, I argued that coastlines themselves are legible lines actively engaged in writing and erasing. That broad understanding of what writing is and does in a wide range of contexts is certainly informed by my background in Fine Art.

JB: Your work is extremely well-researched and clearly object- and place-oriented. At the same time, however, there is also strongly personal and subjective, yet not overtly autobiographical or confessional. Would you define your poetic work as “scientific-lyric”, or is that a misnomer? In all cases, there is a wonderful lyrical twist in your rearrangement of documentary and scientific material, and not only because “wind” and “water” or “clouds” and “sea” are conventional poetic topics. You do much more than just “poetically write” on these themes or looking for symmetries between art and science…

JR: For me, reading, writing, teaching, and performing are all intertwined processes. My research often involves sited, or embodied research, in the form of walking, for example. This contextual enquiry is often, but not always, followed by library- or archive-based research. Neither mode is more or less personal or subjective than the other.

My writing about place is always writing about displacement and its attendants: desire, longing, and loss. I am a migrant. I am often writing about past places, or temporary places. Places and times which could never be mine. I am warry of the lyric ‘I’. My ‘I’ is always already a displaced person, queer, foreign, and fractured. When I write ‘I’ I don’t always mean me. Sometimes my ‘I’ is fictional. Sometimes I wish to refer to a subject condition which is bordering on plural, which is not quite ‘we’. I often incorporate found text in my work as a way creating a multiplicity of voices, ways of knowing, and subject conditions. The introduction of scientific writing may interrupt the lyric, alerting the ear to danger. At the same time, the lyric may dislocate the scientific text, dislodging deep-seated presumptions of objectivity.

JB: Although it does not make sense to stick to a strong divide between genres in your writing, one has the impression that the notion of poetry is what unites the various aspects, facets and planes of your work, and that perhaps from the very beginning. Yet we know the notion of poetry has become extremely vague and perhaps problematic given the equally strong political and ecological dimensions of your work. Is there any definition of poetry you feel sympathetic to, and how do you see the added value of poetry to your critical thinking?

JR: I am averse to definitions. I prefer an ongoing system of definings: fluid, flexible, fit for purpose, for a particular moment, then dissolving and reformulating as circumstances change. My critical thinking is, as I have said, informed by material, line, place, displacement, desire, fracture, voice, and interruption. Poetry is one way to get that critical thinking onto a page or a screen, or into the air through my body. That could be one way of defining poetry. There are other ways. What I’m most interested in is process. My compositional process incorporates strategies from poetry, for sure. And also from prose, essay, rhetoric, walking, drawing, collage, cartography, photography, computer programming, scriptwriting, performance art, animation, translation… whatever tools come to hand. I am a collage artist. That could be another way of defining my writing.

JB: You have chosen from the very beginning to elaborate and publish your writing in a digital environment, yet never in an exclusive way, since most of your poetry is available in different media formats (performances, public readings, audio fragments, online publications, and last but not least classic, highly attractive and above all very affordable collections of poetry in print). How do you see and implement the relationship between these formats? Or more precisely: is the transmedial character of your work something that is programmed from the very beginning, or do you start in a given medium and then continue to explore changes and expansions? And do you consider that each separate publication format, even if it never a completely standalone work, can or should exist outside the network it is part of?

JR: I don’t start in any particular medium. I start in the world. That sounds grand. But I mean it in a straightforward way. I’m in the world, living, walking, talking, listening, looking, cooking, reading, teaching, and that’s where it starts. Some sound, or image. A shift in the light. A strange turn of phrase. Or an error, even. A problem. An unanswerable question. A chance encounter, with a book, or an animal, say. Chance has a lot to do with it. I have strategies for bringing these starts into being, but often they just happen. The trick is to recognise them and find some way to capture them immediately before they slip away. This is most often done with a pen and/or a phone camera. Sometimes I have to mumble phrases over and over until I get home. I’m a compulsive note-taker. Sometimes I don’t know something has started. Sometimes I make the same note four or five times but don’t notice till later. Sometimes I know right away. Then, a long, iterative compositional process begins. As I work through iterations, across forms, the forms inform future iterations. I’m learning as I go, about how the text performs in different contexts. This is one way of defining practice-led research. There are others. The order the research outputs appear in varies with each project. A lot depends on the myriad of partners involved in each piece – editors, publishers, curators, funders, etc. They’re all part of the aforementioned world. In any case, readers will always come to the work wherever they come to it, and most will never experience all of it. Even I have already forgotten half of it by now. I work with variable text. I have to be okay with partial readings, and so does everyone else.

JB: Your beautiful website (https://luckysoap.com/), a “map” of your past and current productions, is clearly a creative work in itself, demonstrating the dismantling of boundaries between creation and research, writing and critique, performance and presentation. What exactly is the role and place of this website in your whole work?

JR: It’s not a creative work. It’s a list of publications, like a CV, with links to research outputs and their publication contexts. It just so happens, in this case, that many of the publication contexts are also online. If it looks creative, that may be because it doesn’t look corporate. I’ve been using the same basic HTML template since 1997 or so. I shudder to think how many links to external sites are no longer working. The boundaries between my web-based CV and my web-based work and the web-based galleries exhibiting my web-based work and the web-based journals publishing my critical writing about my web-based work may be less visible than the physical delineations between book, journal, gallery, and art object, but those structural boundaries are all still there in the world. My contributions to dismantling boundaries are lodged within the works themselves, not in the index that points to them.

JB: As a writer, and of course also a visual and performing artist, do you feel that the institutional context in which you are working, is more that of a visual artist than that of a writer, in the conventional sense of the word? Your work is commissioned by a wide variety of institutions (festivals, galleries, research institutions, literary organizations), yet despite the diversity of this institutional (and thus media) setting, your work has proven capable of producing an exceptional homogeneity. Is this the result of the use of certain themes and techniques (for instance site-specific ecologically oriented writing) that are “institution-insensitive” so to speak, or does it reveal something deeper on the changes that are taking place in these institutions themselves?

JR: I am not working from within any one institutional context. I am almost entirely without discipline. Even as an undergrad in art school, I majored in Studio Art, but also took courses in Art History, Anthropology, Philosophy, Geology, and Religion. I didn’t go to grad school; I went to work in the corporate world instead, for a few years, to pay off my student loans. And then, as you say, I worked with a wide variety of public-facing institutions. By the time I began my PhD research I had fifteen years of independent practice under my belt. I was not situated in any one department. Or, if I was, I didn’t pay any attention to the point of now having no recollection. I was working in the web, a medium which barely existed when I was an undergraduate. My primary methodology was Performance Writing, which interrogates the performance of texts across formal, disciplinary, material, social, and political contexts. Here perhaps we arrive at the answer to your question: If my body of work has any coherence to it, it is due to an abiding preoccupation with process and pragmatics rather than with any particular institutional frameworks.

JB: Technological obsolescence is a key issue in the digital environment, not only from an ecological and social point of view (we all know the cost of the ecological footprint of the computer business just as we don’t ignore the widening gap between those capable of catching up with the permanent creative disruption of the field and the others…), but also from an artistic point of view, with many works from older (sic) periods no longer accessible, not even to their own creators. How do you address these problems in your own work and how do you approach these questions in your collaboration with commissioning institutions?

JR: I have been making web-based work continuously since 1995. My work retains a certain lo-fi sensibility from that period, which has inadvertently helped preserve it. Only one of my works has disappeared entirely. In that case, the commissioning body insisted on hosting it on their server and then did not maintain that server. Otherwise, I host everything on my own server and keep backups offline. This enables me to make slight tweaks to older works to keep them going. There are a few pieces held in collections than no longer work perfectly, but the updated versions on my server generally work fine. I have three works which incorporate the Google Maps API which are no longer fully functional due to changes in Google’s terms of use. I could keep them going, but I refuse to give Google a credit card number. In the case of ‘in absentia,’ the work itself is about gentrification, so if the piece no longer works due to corporate gentrification, the piece has perfectly performed its own message. I am content with this.

JB: One of the most striking features of the growing encounters between writers and artists, once again in the traditional sense of these words, is their commitment to curation and curatorship. What are for you best practices in this field, and do you think that it is possible to implement curatorship in the very creative process, that is before its actual exhibition, performance or publication? Or do you think that modern writers like you are already doing this job? If so, how would you describe your “self-curating” practice?

JR: I relish the opportunity to work with good curators, editors, publishers, producers, and collaborators. Sometimes a curator asks me if I have an idea and suddenly, I have one, where I could swear I didn’t have one moments before. Sometimes I think my idea is one thing and an editor patiently informs me that it could be something else entirely, opening a whole new world of possibility. I have benefited so much from this sort of input. I’m always looking for ways to amplify the voices of other writers and artists, through mentorship, collaboration, hosting in-conversation events, or writing introductions. I don’t think of any of that as curation, just part of being part of a community.

Louvain/Settle (North Yorkshire), September 2021